Missing the Magnificent Seven

“Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack.” —Jack Bogle

However magnificent the Magnificent Seven tech firms may be, trying to find the next shiny object in the stock market is a fool’s errand. Remember what happened to Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick? Despite the captain’s three attempts to catch it, the great white whale destroyed the Pequod and killed all but one of the crew. Beware.

Maybe your neighbor bought Nvidia early and made a killing. If you’re an equity index investor, so have you. As of September 30, 2023, the Magnificent Seven—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla—accounted for nearly 32% of the S&P 500 index. And you own them all.

There is an old saying on Wall Street that the market is driven by two emotions: fear and greed. We beg to differ. Rather than greed, we believe there are actually two types of fear. First, there’s the typical fear of a permanent loss of capital. Second, there is the dreaded fear of missing out.

Warren Buffett insightfully described this condition in a 2018 interview with CNBC: “People start being interested in something because it’s going up, not because they understand it or anything else. But the guy next door, who they know is dumber than they are, is getting rich and they aren’t.”

In the context of personal financial planning, successful long-term investing has nothing to do with trying to find the next monster stock. It has everything to do with temperament: specifically, how you respond to the constantly fluctuating prices—volatility—that are part of the package deal when you own equities.

Stock market whales are rare

Consider the astonishing findings of Hendrik Bessembinder, a professor at the University of Arizona. He sought to answer this question: Over time, do most individual stocks outperform the riskless asset of cash (Treasury bills)? He found the answer to be an emphatic no.

Bessembinder defines shareholder wealth creation as the excess return of stocks over cash. His research found that between 1926 and 2019, half of all shareholder wealth creation came from just 83 out of 26,168 companies (0.32% of the total) that were publicly traded during that period.

Even more astonishing, he found that all the wealth creation in the stock market since 1926 was attributable to about 1,000 of the top-performing stocks—or about just 4% of the total. And the concentration of shareholder wealth has increased over time, with a small number of firms contributing more to overall wealth creation.

Moreover, investments in the majority of stocks (about 58%) led to reduced rather than increased shareholder wealth. Nonetheless, Bessembinder reported, “Shareholders who took on the risk of investing in the public U.S. stock markets between 1926 and 2019 were rewarded by an aggregate wealth increase of over $47 trillion, as compared to a Treasury bill benchmark.”

While many individual investors may prefer the potential for outsized returns from concentrated portfolios, broad diversification remains a prudent strategy for most investors due to the uncertain nature of market outcomes.

Always a bigger fish

The Nifty Fifty stocks of the 1960s and early 1970s were known as one-decision stocks because investors could supposedly buy and hold them forever. Even though this group sported very high price-to-earnings ratios relative to the overall market, the thinking then was that you would enjoy consistent earnings and dividend growth—forever. Let’s look at the experience of General Electric and IBM, then two stalwart, household names in the Nifty Fifty, over the last five decades.

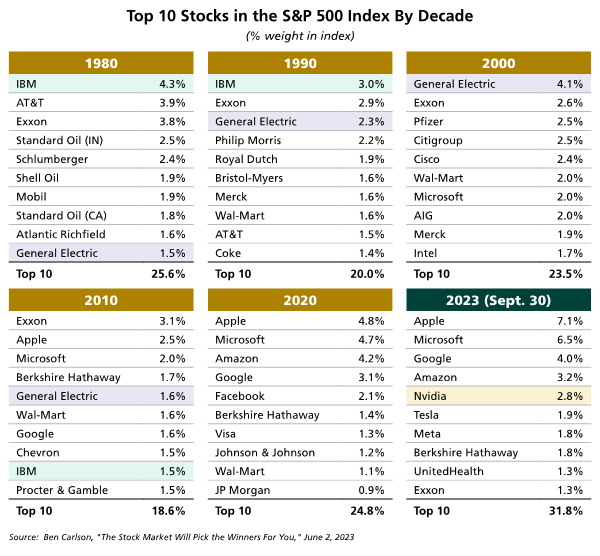

Founded in 1911, IBM was the most valuable company in the country in both 1980 and 1990. After dropping out of the top 10 in 2000 and then reemerging at #9 in 2010, the 112-year-old company disappeared from the list of top stocks, ranking #54 in October 2023.

General Electric, founded in 1892, moved from #10 in 1980 to the most valuable in the country by 2000. It slipped down to #5 in 2010 and then fell completely off the list. Today, it occupies the #58 position. Notice the striking transition from predominantly oil stocks in 1980 to technology stocks today.

On the rising end of the spectrum, Nvidia is the stock market darling of 2023 with a year-to-date return of 177% as of October 27, 2023. It’s currently #5 on the list despite being nowhere in the top 10 just three years ago.

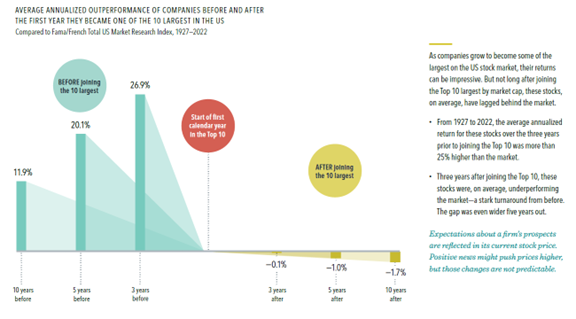

Lest you be tempted to buy the Magnificent Seven today, consider this: Research from Dimensional Fund Advisors shows that just three years after joining the Top 10, stocks generally start underperforming the market—with this underperformance persisting five and 10 years thereafter.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors

Indexing is still the best bet

Princeton economics professor Burton Malkiel, author of “A Random Walk Down Wall Street,” has been one of the strongest proponents of indexing. Here’s his perspective from a Wall Street Journal op-ed in September 2023:

The basic idea of efficient markets isn’t that prices are always correct. In fact, they are always wrong. What efficiency implies is that information is reflected in prices without delay. And the current tableau of market prices reflects the combined judgment of hundreds of thousands of investors, including those of the research departments of the most influential firms on Wall Street—as well as the galaxy of active managers who run mutual funds and institutional portfolios. It’s rare for an individual manager to make correct bets against the wisdom of the market. And even when it does happen, it doesn’t last. More than 90% of active managers fail to beat the market over 10- and 20-year periods. It isn’t impossible to beat the market. But if you go active, chances are you’ll underperform.

Today it’s the Magnificent Seven. In the late 1990s it was the dot-com stocks, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s it was the Nifty Fifty. Same concept, different eras. Chasing the Magnificent Seven is a loser’s game, but you can win—and be a successful investor—by refusing to play.

Jack Wyss, a student at Harvard College (class of 2025), contributed to this essay.