Responding to Rising Inflation

What tactical changes should you make to your portfolio in response to the prospect of rising inflation? Answer: None.

Inflation basics

Let’s start by acknowledging that some inflation over time is completely normal and expected. Expected inflation is already embedded in nominal asset prices. Therefore, only unexpected inflation represents the risk of eroding real asset values in the future.

As Nobel laureate Milton Friedman noted, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Friedman argued, based on empirical data, that one could not find inflation anywhere in the world that was not caused by a prior increase in the money supply or in the growth rate of the money supply.

Since M2—the most basic measure of money supply—has increased 34% from February 2020 to August 2021, Friedman’s model suggests that an increase in inflation is highly likely over time—and which will not be transitory in nature.

Purchasing power

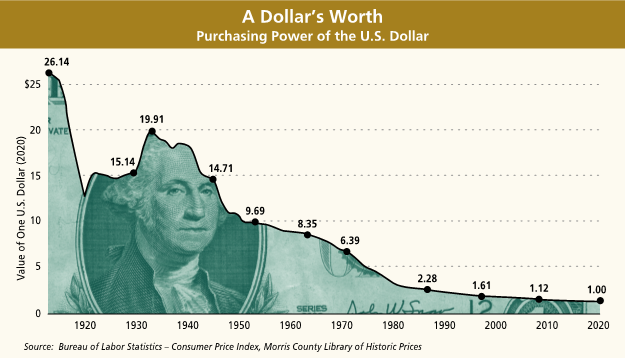

Investors are naturally concerned about inflation and its negative impact on the purchasing power of their portfolios. But preserving the dollar value of a portfolio is never an adequate goal, because inflation constantly erodes that value. With 3% inflation a year, the cost of living doubles every 25 years, and investors who merely preserve their principal will lose half their purchasing power over that period. The goal must be to preserve and grow purchasing power.

Indeed, over the past 30 years, a period of relatively moderate inflation in the U.S., the purchasing power of $1 has been cut very nearly in half.[1]

Empirical evidence

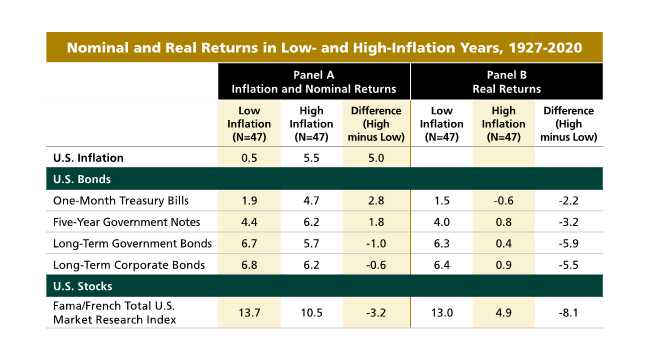

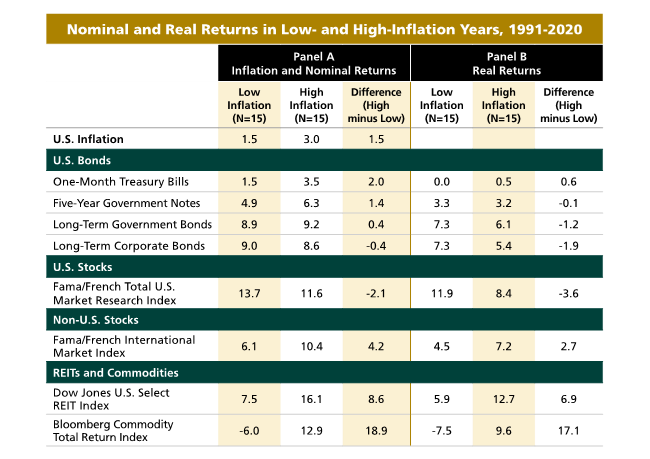

In a recent series of articles,[2] researchers from Dimensional Fund Advisors analyzed the nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) returns across 23 global asset classes over two time periods: 1927 to 2020 (94 years) and the most recent 30-year period, 1991 to 2020. The shorter time period includes an expanded list of asset classes (e.g., international stocks and bonds, commodities, real estate investment trusts).

The longer study includes the Great Depression (1929 to 1932), when the United States experienced deflation, as well as several years with double-digit inflation in the 1940s, 1970s and early 1980s. Over the entire time frame, the average annual inflation rate was 5.5% for years with above-median (“high”) inflation, compared to 0.47% in years with below-median (“low”) inflation.

In the tables below, Panel A shows average annual inflation and nominal returns, while Panel B shows average annual real returns. Table 1 displays the results for the full 94-year period, while Table 2 covers the most recent 30-year period.

The primary conclusion of the Dimensional study may be surprising: Except for one-month T-bills, all asset classes had positive average real returns in high-inflation years. Here are some other findings:

- Most asset classes had positive average real returns in both low- and high-inflation years. This was true over both periods. It’s worth noting that for the most recent 30-year period (1991-2020), U.S. inflation has been relatively low and stable.

- While average real returns were lower in years with higher inflation for most assets, many of the differences are not statistically reliable, especially among non-bond assets and in more recent years.

- In the few cases where the correlations were reliably positive, such as for energy stocks and commodities from 1991 to 2020, the assets’ returns were around 20 times as volatile as inflation and more than half of their nominal-return variance was unexplained by inflation. Therefore, both assets are too volatile to be an inflation hedge. (See our “Gold Misconceptions” for a fuller explanation of gold’s ineffectiveness as an inflation hedge.)

Equities: The efficient, effortless long-term inflation hedge

Historically, equities have been the most efficient and effortless long-term hedge against inflation. Since companies must contend with inflation in their owns costs, the conclusion seems counterintuitive and demands an explanation. Actually, it’s quite simple.

In addition to their ceaseless innovation, the great companies of the world have historically been successful in passing along their increased costs to consumers. Thus, these companies—mainstream equities—manage to record higher sales, earnings and dividends over time.

Since year-end 1971, the S&P 500 is about 40 times higher, earnings are up 19-fold, and dividends are about 19 times higher—yet inflation is a little less than 7 times what it was 50 years ago. This is the quintessence of why we own equities in the first place. To put it quite simply, all you needed to do from 1971 until today to take full advantage of that growth was to be invested broadly in equities and immediately reinvest any dividends. By paying taxes on your dividends and gains from uninvested funds, you enable the value of your investments to compound to the fullest extent.

Responding to a potential increase in inflation

In “Responding to Rising Rates,” we emphasized the importance of having a written, date- and dollar-specific financial plan; outlined our simple asset allocation methodology; encouraged embracing the mindset the mindset that your portfolio is the medium to fund your plan; and emphasized the primacy of behavior (faith, patience and discipline) as the ultimate key to success.

In short, there is nothing to do and no need to respond to a forecast rise in inflation.

Behavioral takeaway

When it comes to achieving your lifetime financial goals, there are only three determinants that truly matter: financial planning, asset allocation and behavior. If you get the first two right, the final—and often greatest—challenge is exercising faith, patience and discipline over time.