Lifetime Tax Planning Amidst Uncertainty

As we know, there are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

– Donald Rumsfeld, former secretary of defense

The Biden administration has floated a set of sweeping tax increase proposals that would affect taxes on income, capital gains, corporate earnings, estates and even wealth. Of course, turning any of these proposals into law is subject to the political process. Given the lack of consensus for some of the proposals, even among Democrats, the likelihood of near-term tax increases is truly unknowable.

Given this uncertainty, how should you adjust your financial planning—if at all? Should you do something now, or is it better to see what happens and then react accordingly?

Practicing rationality under uncertainty

Successful financial planning and investing requires the practice of rationality under uncertainty, because we plan and invest for an essentially unknowable future. Given the complexity of the U.S. tax code[1], coupled with countless potential outcomes, we attempt to simplify the framework.

Direction of overall tax rates: Higher?

The national debt has doubled in the last decade, increasing from $14.3 trillion in July 2011 to $28.5 trillion in July 2021. Moreover, the Congressional Budget Office forecasts that during the 2021 fiscal year, the United States will record a $3 trillion deficit ($6.8 trillion of expenditures less $3.8 trillion of tax revenue). Over the next 10 fiscal years, the CBO projects a $12.1 trillion total deficit ($63.4 trillion of expenditures less $53.1 trillion of tax revenue). Those are huge numbers.

Trillions of dollars in additional federal spending since the Covid pandemic began must eventually be collected. Additionally, while government spending has historically been fairly steady at about 20% of gross domestic product, the administration’s spending proposals would raise it to about 25%.

We assume that a significant chunk of the current federal spending spree will lead to permanent budget entitlements. Similar to Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, these are nondiscretionary, untouchable programs. These entitlements have to be financed somehow.

Accordingly, our overarching assumption is that taxes will rise over time. No one knows which ones, but we believe that funding these proposed expenditures will likely require significantly higher tax revenue from multiple sources.

Time frame: Planning for life rather than death

For decades, the estate planning profession has focused on minimizing taxes for a person’s estate upon death. Given some of the current proposals, including wealth and higher capital gains taxes, a fundamental shift in the estate planning time frame is now essential. Specifically, we recommend that you consider a lifetime planning horizon rather than optimization on death. Here, we focus on income taxes and capital gains taxes.

Income taxes

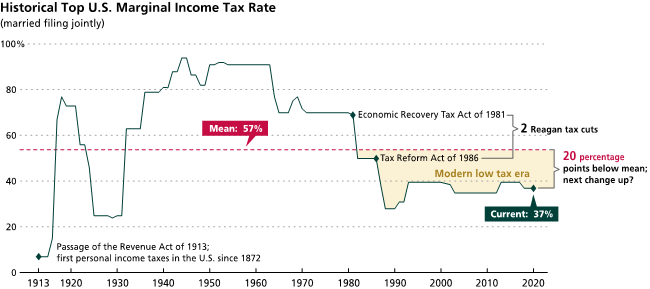

Wealthy taxpayers have enjoyed historically low tax rates since 1986, when the top income and capital gains tax rates were both set to 28%. We believe those rates will likely rise, perhaps in the near future.

One simple way to hedge against the prospect of higher future taxes is to convert a traditional IRA, where income taxes are paid at the time of distribution, to a Roth IRA, where taxes are paid at the time of conversion—and thereafter are completely tax-free. In 2020, we wrote about a unique opportunity to take advantage of historically low tax rates. For those who can afford to pay the associated income taxes today, and subject to the important “bracket-topping” consideration, we reiterate this recommendation.

Some companies have 401(k) plans that allow after-tax contributions of up to $58,000 per year, with the opportunity to convert some or all of the money to a Roth through a “mega-backdoor” Roth conversion. You should check to understand all of the options that are available under your company’s plan.

But be warned: Even Roth conversions have been caught in the net of proposed tax changes. Lawmakers are considering restricting Roth IRA account sizes, ending Roth IRA conversions, and/or forcing payouts from accounts exceeding a certain size. One reason is because of how the current rules can be exploited. For example, ProPublica revealed that Peter Thiel, a PayPal Holdings founder, used a Roth IRA to grow some $2,000 worth of low-cost pre-IPO shares to $5 billion. The shares gained tremendous value over time, generating tax-free proceeds that Thiel reinvested, increasing his Roth account value even further. If not withdrawn early, that money could be shielded from tax forever.

- Planning tip: Your tax adviser can help you minimize taxes upon conversion by “bracket-topping,” where you convert enough of your IRA to go to the edge of your existing tax bracket—or, if you feel strongly about higher future tax rates, even the next bracket. For example, in 2021, a married couple with $180,000 in taxable income is in the 24% marginal rate bracket, which starts at $172,750 and caps out at $329,850. In this case, the owner could convert up to $149,850 into a Roth IRA without moving to the 32% bracket.

Capital gains taxes

The capital gains tax currently applies to the appreciation of investments when sold. Capital gains taxes depend on one’s federal income tax rate, meaning that retirees may be in a lower capital gains bracket now than they were in their working years. Today’s top capital gains rate is 23.8%, but Biden seeks to increase it to 43.4%.

Biden also seeks to eliminate the “step-up in basis,” which is a tax exemption that minimizes capital gains taxes on inherited assets. For instance, if someone purchased shares of a stock at $5 that appreciated to $50 by the time of the person’s death, heirs would pay capital gains taxes on future sales based on the $50 stepped-up cost basis rather than on the original price of $5.

The administration has also proposed reducing the current federal estate generation-skipping transfer and gift tax exemption of $11.7 million per individual ($23.4 million per couple). The estate of someone who dies today with $10 million in gains on appreciated stock pays neither capital gains nor federal estate taxes, assuming none of the lifetime estate exemption has been used. Under the proposed changes, this estate would be subject to a 43.4% capital gains tax on the amount of appreciation, less a $1 million exemption, and federal estate taxes.

Rather than selling appreciated assets during their lifetimes, many wealthy investors have long employed a “buy, borrow, die” strategy to avoid capital gains taxes. In the future, such a strategy may be considerably less beneficial.

- Planning tip: With the potential for a capital gains tax increase, if you’re considering a sale in the next 24 months of capital assets (such as a business) or shares of highly appreciated stock in a taxable account (such as inherited stock or a concentrated stock position), we recommend that you and your tax adviser perform an analysis to see if accelerating the sale might be beneficial.

Controlling the controllables

A common behavioral mistake is to let the tax tail wag the investment/financial planning dog. People often go to extreme lengths to avoid realizing capital gains today so they won’t incur capital gains taxes that have to be paid today. We believe it’s well worth considering locking in today’s historically low tax rates by accelerating your realization of income and capital gains. By the time the known unknowns become known knowns, the window of opportunity will likely be shut.

Important Legal Disclaimer: Keating Wealth Management is not an accounting or tax advisory firm and is not qualified to render tax advice of any kind. Keating Wealth Management is not a law firm and is not qualified to render legal advice of any kind. Moreover, estate planning is a specialty area that requires subject matter experts to advise on the particulars of a given situation, and each state has its own estate tax law. The best course of action is to consult relevant experts in your state.

[1] The discussion here is limited to federal taxes. State taxes and estate law vary considerably, and you should consult subject matter experts in your state to consider the implications based on your individual facts and circumstances.