International Equities Allocation: How Much and Why?

Once you have determined the appropriate allocation to equities in your portfolio, the next question is which securities you should own and why. There are countless ways to slice and dice the asset class: by size, by style (value or growth), by sector, by fundamental factors such as dividends and volatility, and so on.

All of that will likely amount to only tiny differences over a multidecade time horizon, so it’s really just noise. Worse, emphasizing security selection reinforces some detrimental behaviors. The most insidious of these, for individual investors, is judging “investment success” by the relative performance of different types of equities, rather than overall progress toward the achievement of financial goals.

Your investment portfolio is a medium to fund your financial plan. And you own equities because, over long periods of time, they have been the best way to preserve and grow purchasing power. Since 1926, equities have a delivered an inflation-adjusted real return of 7% for large-company stocks and 9% for small-company stocks—double and triple the real return for bonds.

There’s one more feature that distinguishes equities from all other asset classes: It’s the only one that monetizes human ingenuity. Think about that for a moment.

You can own 3,654 individual U.S. equities and have exposure to stocks of all sizes through a fund such as the Vanguard Total Stock Market index mutual fund (ticker symbol VTSAX) or exchange-traded fund (VTI). With large-cap stocks comprising about 80% of the portfolio, mid-caps about 14%, and small- and micro-caps accounting for the balance, you can enjoy complete sector diversification at an annual cost of just 4 basis points (0.04%). Not to be outdone, in August 2018, Fidelity completed the race to zero by launching similar index funds that charge no fees at all.

But how do international equities fit into the equation?

We live in a global economy, and human ingenuity is not limited to the United States. There are dominant companies in developed markets such as Japan, the U.K., France and Germany, as well as in “emerging” markets such as China, South Korea and India. Given a world population of about 7.6 billion people, only about 4% of whom live in the United States, international equities offer you the opportunity to share in the profits of companies that serve the remaining 96% of the world. Diversification is a secondary but helpful benefit.

The much trickier question is what percentage of an equity portfolio should be allocated to international equities. Using market capitalization as a starting point, some academics recommend as high as 50%. But we suggest a mere 20%. To be sure, this is not a mathematically derived number. Instead, here are five factors supporting the reasoning:

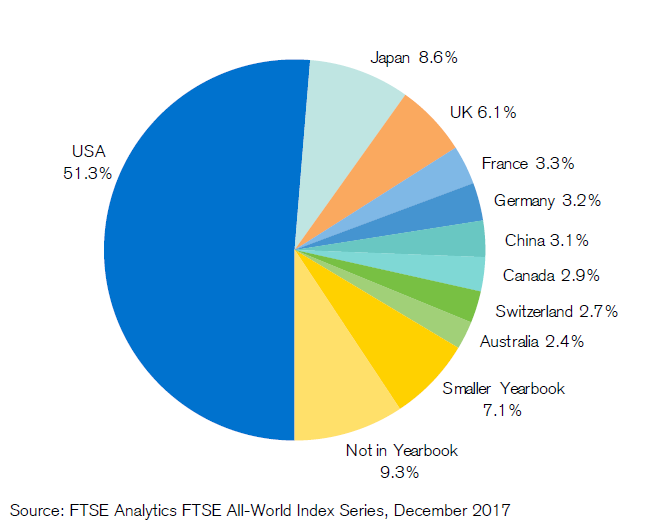

1. Market capitalization is a more relevant weighting consideration than gross domestic product. At about $19.4 trillion in nominal GDP as of 2017, the United States represents about 24% of the $79.9 trillion global total, according to the International Monetary Fund. At the same time, U.S. public companies accounted for about 51% of 2017 global equity market capitalization, according to Credit Suisse. (See image below.)

2. Large American companies derive a significant share of their revenue from outside the United States. In 2017, about 43% of S&P 500 companies’ sales came from abroad, according to Standard & Poor’s. Since these large companies implicitly provide exposure to the global economy, an American investor can adjust the allocation percentage downward.

3. The long-term correlation of returns between U.S. and foreign equities is extremely high. For the 10 years ending in 2017, the correlation between the S&P 500 ETF and the MSCI EAFE ETF, covering Europe, Australia and the Far East, was about 88%, while the correlation between the S&P 500 ETF and the MSCI Emerging Markets ETF was about 80%, according to iShares. When you couple this high correlation with currency, economic and societal risks, Vanguard founder John Bogle argues that an American investor doesn’t need to own any international stocks.

4. Most investors have a home country bias. The tendency to want to invest in one’s own backyard is neither unusual nor surprising, and it’s a worldwide phenomenon. Understandably, most people want to own companies whose products and brands they know and trust.

5. It’s simple. This might be the most important reason of all. Round numbers are easy to understand and remember, and picking one avoids the fool’s errand of trying to calculate a mathematically precise “optimal” allocation amidst widely diverging viewpoints.

Relative Share of World Stock Markets (December 31, 2017)

As with your domestic equity allocation, ideally you should spend almost no time thinking about specific security selections. In addition to the endless ways of looking at U.S. exposure, geography and currency risk join the mix of factors to analyze when working within the relative performance mindset. It’s an analysis that is not worth the effort when you can just buy the whole asset class very cheaply through an index fund.

As with our example for the U.S. market, there is a simple way to own the leading businesses of the rest of the world. Through either a Vanguard Total International Stock index mutual fund (VTIAX) or ETF (VXUS), at an annual cost of 11 basis points (0.11%), you can own 6,354 individual non-U.S. equities with exposure to Europe (about 43%), Asia (about 29%), emerging markets (about 21%) and Canada (about 7%). Fidelity recently launched a similar international equity index fund with no fees.

Now let’s take a giant step back to put the entire issue into proper perspective. The percentage you have allocated to international equities is ultimately irrelevant to the long-term, real-life outcome you will experience as an investor. Here’s what really matters, in order of importance:

1. Whether you have a date- and dollar-specific financial plan that is updated regularly.

2. Whether and to what extent you own equities rather than bonds.

3. Your ability to stick with your plan rather than succumb to panic and abandon it.

Collectively, we believe these three factors explain 95% of the benefits you will enjoy—or not, as the case may be. Choose wisely.

Behavioral Takeaway

Mental accounting occurs when a person views various sources of money as being different from others. Although compartmentalizing international equities may be convenient for analytical or segmentation purposes, the choice of which equities to own is substantially less important than the decision about how much of a portfolio should be allocated to equities, as well as the investor’s ability to avoid costly behavioral mistakes.