Reaching for Yield

“Reaching for yield is very stupid. But it is very human.” —Warren Buffett

With the recent demise of Silicon Valley Bank, the TV commentariat reduced the cause of the collapse to the sound bite of “risky bets” made by management.

What exactly were these risky bets? What toxic, radioactive assets did SVB have on its balance sheet?

The assets were primarily U.S. Treasury bonds and U.S. agency mortgage-backed securities—both backed by the full faith and credit of the United States. In other words, from the perspective of default risk, these were among the safest securities on the planet.

As to the risky bets, SVB had purchased longer dated maturities, which carried the associated risk of rising interest rates and declining prices (by not hedging most of the interest rate risk). When forced to sell these supposedly safe securities to generate cash for fleeing depositors, SVB realized losses that wiped out its stockholders’ equity.

The great, timeless lesson from this debacle: Reaching for yield is one of the cardinal sins of investing. And as Buffett succinctly states, it’s both very stupid and very human.

Or, to restate the concept as an iron law of the capital markets: The combination of safety, liquidity and high yield does not exist, because it cannot exist.

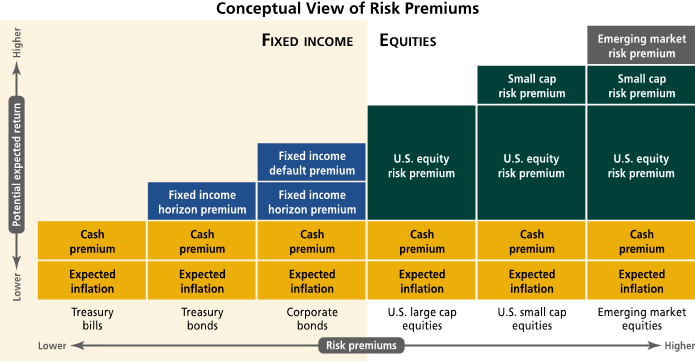

Conceptual view of risk premiums

Using the building block approach of risk and return developed by Ibbotson Associates, the expected return on an asset class represents the sum of the current risk-free rate (inflation plus the 30-day Treasury bill rate) and one or more historical risk premiums as compensation for each element of risk, as illustrated below.

A Treasury bill is a U.S. government debt obligation backed by the Treasury Department with a maturity of one year or less. As noted earlier, the T-bill rate factors into the risk-free rate. Using Ibbotson data going back to 1926, the risk-free rate has typically been about 3.5%, consisting of 3% inflation plus a 0.5% cash premium (the T-bill rate).

Treasury bonds add a fixed income horizon premium, which is the extra return required to make it worthwhile for investors to hold longer maturities—essentially, compensation for interest rate risk. Finally, corporate bonds add a fixed income default premium, which is the extra return required by investors to compensate for counterparty risk by the bond issuer.

As an investor, you can’t enjoy absolute safety and high returns; they’re mutually exclusive. Instead, the reach for progressively higher yields requires taking on incremental elements of risk. The enterprising fixed income investor may try to time the direction of interest rates and/or attempt to identify mispricing in bonds, but history is littered with “sophisticated” institutional investors who reached for yield—in all its forms and across every market environment—and ended up badly burned or wiped out.

The yield problem with fixed income

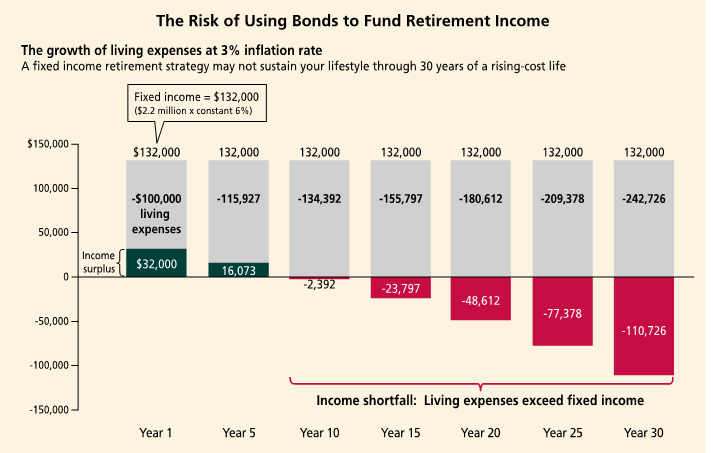

Consider a married couple in their first year of retirement with a $2.2 million nest egg, $50,000 in combined Social Security income, and annual living expenses of $150,000. They need their portfolio to generate $100,000 in annual income to fund the difference between their annual Social Security benefit and their living expenses. Further, the couple has a self-described “conservative” risk profile, and they are attracted to the comfortable “safety” of bonds, where there is no perceived risk to principal. They want to clip the coupon of yield and use all of it to fund their living expenses.

Let’s assume that this couple could invest their savings in high-quality, long-term corporate bonds yielding 6% (the compounded return over the last nine decades). The first year, they’d have a significant cushion, since their investment income of $132,000 ($2.2 million x 6%) would be a third more than their income needs of $100,000. (And for simplicity of illustration, we’ll assume they spend those extra funds rather than reinvesting them.) So far, so good.

Next, consider that the couple’s living expenses will increase 3% per year, the historical average inflation rate over the last 90 years. At that rate, their cost of living will double over 25 years, and what costs $100,000 today will cost $242,726 in 30 years. The erosion of purchasing power is slow, insidious and constant—yet all but invisible on any given day.

For about the first 10 years, the couple would have enough income. (Perhaps, in the real world, they might have saved some of their rapidly declining surpluses). But as the following chart illustrates, after year 10, the couple’s living expenses would dramatically outstrip their annual fixed income of $132,000. As they grow older, they turn upside-down financially—not a place anyone wants to be.

To be sure, we’re not advocating for an all stocks, all the time approach to asset allocation. Retirees should set aside an amount sufficient to cover two years’ worth of living expenses to enable the suspension of equity withdrawals if a long or steep bear market strikes relatively early in retirement. People also need to set aside a capital sum for any known commitments payable within five years and invest it in bonds with a corresponding maturity. In most circumstances, the remainder of the portfolio should be invested in equities.

The chimera of higher yield without higher risk

Market prices reflect the aggregate expectations of all market participants, including expectations about inflation and interest rates. Simply put, yields are what they are. What you believe you need in yield from your portfolio and what’s available from the market are two different concepts.

Merriam-Webster defines chimera as “an unrealizable dream.” Such is the case the case for any bond that purports to offer safety, high yield and liquidity in the same security. Short-sighted yield chasing is the eternal chimera of higher yield without higher risk. Investors say they want safety and income; what they really want is all the income they can get and the illusion of safety. Reach for yield at your own peril.

Behavioral takeaway

Narrow framing involves making decisions without considering all the implications. In a financial context, it means evaluating too few factors regarding an investment. Reaching for yield as an end in itself ignores the risks associated with the sources of incremental return. Moreover, seeking to lock in a yield today that matches a current cash flow requirement ignores the significant erosion of purchasing power over time due to inflation.