Hedge Fund Mirage

Hedge funds have had a lot of bad press lately, and it’s coming from all quarters.

First, there is disappointment in the category from high-profile investors such as public pension funds. The most recent headline-grabbing news was the decision by the New Jersey Investment Council to cut the state’s target hedge fund commitment by more than half—from 12.5% down to 6%. With nearly $72 billion in pension fund assets, New Jersey had $9.1 billion committed to hedge funds at the end of May.

New Jersey’s move was particularly striking because the state had been one of the more enthusiastic proponents of hedge funds. This action follows exits from the asset class earlier this year by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and New York City’s public pension fund, among others.

Next, there is the impact on the managers whose assets are being redeemed.

The growing exodus from hedge funds has adversely affected the assets under management of some of the largest and highest profile names in the industry, including:

- Tudor Investment Corp. (assets down to $11 billion from $14 billion at the end of 2014).

- Brevan Howard, long regarded as one of the largest, most influential and most consistently performing hedge funds in Europe (assets down by more than half to $19 billion from $42 billion two years ago).

- Och-Ziff Capital Management Group, the largest publicly traded hedge fund manager in the U.S. ($42 billion in assets as of April 1), which has experienced billions in outflows and said in its most recent earnings report that “this trend will likely continue to some extent for some period of time.”

As if all this weren’t bad enough, hedge fund managers are the embodiment of the “top 1%” that have become punching bags for certain political groups and the media.

The reasons for the outflows include bad performance, of course. We’ll get to that in a bit. But first, let’s quantify the damage to the industry.

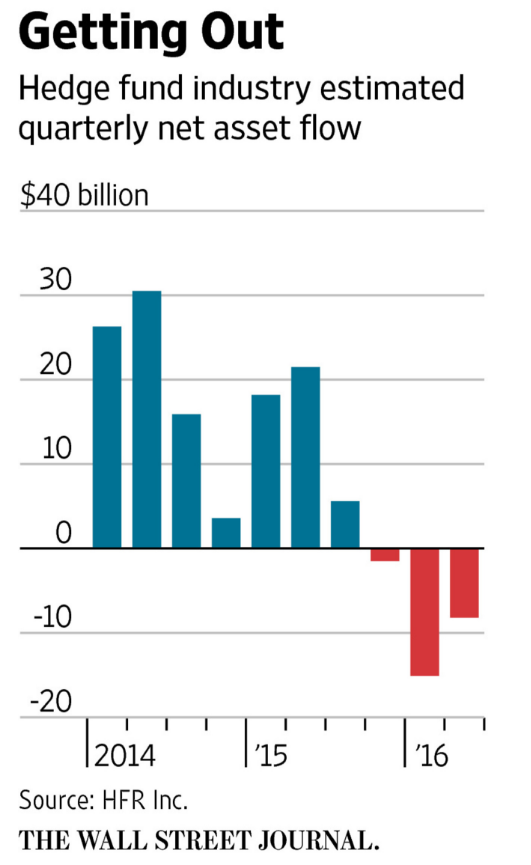

According to Hedge Fund Research, Inc., the hedge fund sector has now experienced three consecutive quarters of withdrawals for the first time since 2009. In the first half of the year, investors redeemed $28 billion from hedge funds, according to data provider eVestment.

Despite all this noise, it’s a drop in the bucket in relative terms. HFR estimates total assets in the hedge fund industry at $2.9 trillion, so the withdrawals in the first half of 2016 represent less than 1% of total assets in the category. And this development really should come as no surprise.

Back in 2012, Simon Lack published The Hedge Fund Mirage: The Illusion of Big Money and Why It’s Too Good to Be True. Lack sat on the JP Morgan investment committee that allocated over $1 billion to hedge fund managers and founded the JP Morgan Incubator Funds, two private equity vehicles that took economic stakes in emerging hedge fund managers. Here are the key takeaways from his book:

- “Shocking but true: if all the money that’s ever been invested in hedge funds had been in treasury bills, the results would have been twice as good.”

- “Although hedge fund managers have earned some great fortunes, investors as a group have done quite poorly, particularly in recent years. Plagued by high fees, complex legal structures, poor disclosure, and return chasing, investors confront surprisingly meager results.”

And yet, since Lack published his exposé, the amount of money invested in hedge funds has nearly doubled. (The book is highly recommended.)

The hedge fund category is very broad, but we want to zero in one specific strategy: long-short equity funds. Alfred Winslow Jones founded the first hedged fund in 1949, with the belief that combining two techniques—buying stocks with leverage (on margin) and selling short other stocks—would result in a “conservative” portfolio.

Morningstar currently counts 133 publicly offered funds, with a combined $34 billion in assets, in its “long-short” equity category.

The recent performance results have been awful. Over the 36 months through June 30, 2016, the average return (as calculated by Morningstar) has been about 2% a year—compared to 11.7% from a stock index fund. According to Hedge Fund Research, an index of equity hedge funds has generated only a 3.1% annual return over the last three years, which is almost as bad as the long-short category.

So the question is: Why would anyone ever want to invest in this type of fund, now or at any time? The industry’s answer: to provide investors with an asset class that is not correlated to the stock market. The underlying assumption is that investors will panic after an equity market pullback (always true), and that the long-short fund is a better way to keep them strapped into their seats and maintain exposure to the asset class.

But does this make any sense? No.

In a recent Forbes article, former editor and now columnist William Baldwin exposed the shoddy thinking supporting the case for long-short funds:

Consider what the [long-short] funds do to reduce risk. They have, on average, a sensitivity to stock market fluctuations that is equivalent to a 50% long exposure. (That could come, for example, from investing the whole wad in long positions, then taking on short sales equal to half that amount.) But there are easier ways to go 50% long. You could just put half your money in cash.

Someone who spent the last three years half in cash and half in a stock index fund—SPDR S&P 500 (SPY) or Vanguard 500 ETF (VOO)—would have landed an annual return just shy of 6%. That’s four points better than what the long-short mutual funds delivered. In short, the long-short customers have allowed a lot of money to slip between their fingers. [1]

In addition to the drag of having only 50% exposure to the market, long-short funds have high fees, including high turnover (an average of 260% per year, according to Morningstar) and high expense ratios (1.9% on average—38 times higher than a typical index fund). As just one example, the Goldman Sachs Long Short Fund—which is not quite two years old—has an annual portfolio turnover of 468% and a 2.4% expense ratio, and it has so far delivered an annual average return of -9%.

History teaches us that the odds of success would not improve even if we could magically choose only the best-performing funds or time the strategy at exactly the right moment. Performance-chasing investors tend to get in at the top and bail out at the bottom; as a result, the return on the average investor’s dollar is often less than the return of the fund itself.

A.W. Jones had it half right: He was not convinced that forecasters could consistently predict the direction of the market, which is what led to his original thinking about ways in which a fund could keep its capital fully invested while having a lower exposure to swings in the market.

But you can’t suppress volatility without suppressing return. The bumpy ride of equities is the reason for their premium returns. There is no alchemy—or hedge fund strategy—that will provide higher return without higher volatility. It has always been thus.

Key Behavioral Takeaway

The overconfidence effect is a well-established cognitive bias in which a person’s subjective confidence in his judgments is greater than the objective accuracy of those judgments, especially when confidence is relatively high. Investing in long-short hedge funds in an attempt to generate higher “risk-adjusted” returns is an example of this bias.

[1] Baldwin, William. 2016. “Scary Results At Long-Short Equity Funds.” Forbes, August 23.